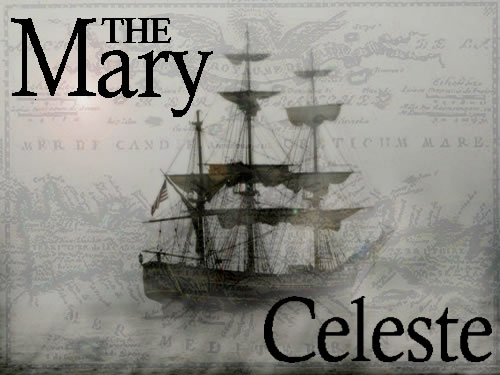

Adventure, Ghost Ship, Mary Celeste, Mystery

Mary Celeste

Mary Celeste

The vast mysteries held by the ocean will never cease to cause fright and caution. Stretching endlessly out before us, the ocean has devoured many ships and planes, caused people to go missing, and swallowed cities whole. For the most part, we can understand the ocean, what happened, but every once in a while, the ocean tosses us a mystery that cannot be explained. A mystery so strange that it causes pause before entering the waters. A mystery that remains unexplained with far more questions than answers.

The Mary Celeste was launched on May 18, 1861 and was registered at Parrsboro on June 10th 1861 under the name Amazon. Her documents indicated that she was 99.3 feet in length, 25.5 feet broad, with a depth of 11.7 feet, and with a gross tonnage of 198.42. She was originally owned by a local consortium of nine people, and was initially captained by Robert McLellan, one of the partners. She was laid in the shipyards at the Bay of Fundy in Nova Scotia, being constructed out of local timbers with two masts.

Her maiden voyage was to carry timber and logs across the Atlantic to London. Before she could set out, the captain fell ill and the departure was delayed. Unfortunately, the captain passed away. With a new captain, John Nutting Parker, the ship took off. Her first voyage was marred by accidents, colliding with fishing equipment near the coast of Maine and hitting and sinking a brig in the English Channel. The poor luck of the ship may have been signs of things to come and sets the stage for how the ship became known as cursed.

For the next few years the ship worked in the West Indies, Mediterranean, and England engaging in what the crew called ‘foreign trade.’ During this time, Captain Parker left the ship and she was taken over by William Thompson. In these years the crew reported no strange occurrences with the ship, saying that she sailed well and was a profitable ship to crew.

A storm in October of 1867 drove the ship ashore. She was so badly damaged that the owners had no choice but to abandon her as a wreck. Alexander McBean of Nova Scotia acquired her as a derelict on October 15th of that year. She quickly changed hands before being bought by Richard W. Haines from New York who repaired the ship, made himself captain, and registered her under a new name, Mary Celeste.

Again, the ship changed hands after being seized by Haines’s creditors in October of 1869. The ship was purchased by a consortium headed by James H. Winchester. The composition of the consortium changed considerably over the next few years but Winchester always remained at the head of it, overseeing a vast expansion and restoration of the Mary Celeste. The consortium named Benjamin Briggs as captain of the ship.

Briggs was a seasoned captain and son of ship captain. He’d married Elizabeth Cobb in 1862 and the pair had two children, a boy Arthur and a daughter Sophia. Briggs had decided to retire from shipping and stay on land with his family but he invested his savings into the refit of the Mary Celeste and was named captain for its first crossing to Italy. Briggs arranged to have his wife and daughter accompany him, while their son, who was in school, would stay back with a grandmother.

On October 20th 1872, the ship was in New York Harbor being loaded with denatured alcohol bound for Genoa. Both Briggs and his wife Elizabeth wrote letters to their mothers telling of their intent to set sail the next morning, promising that they would send correspondence whenever they got a chance. Those letters were the last time anyone seen or heard from anybody on the Mary Celeste. On November 7th, after waiting out poor weather conditions, the Mary Celeste raised anchor and sailed out to sea.

At about 1pm on December 4th, 1872, Captain David Morehouse of the Canadian vessel Dei Gratia, came on deck to the reports of the helmsman of a vessel about six miles away heading unsteadily towards them. The strange set of the sails and her erratic movements led Morehouse to believe that something was wrong. As the ship got closer they could see no people on deck nor would the ship reply or acknowledge any of their signals.

Morehouse sent two mates to investigate. First mate Oliver Deveau and second mate John Wright quickly established that the name on the stern of the wayward ship was Mary Celeste. The pair boarded and found the ship deserted. The sails were in poor condition with some missing and some of the rigging was damaged. Ropes were hanging over the sides but the main hatch was secure. The ships single lifeboat was missing.

As the pair investigated deeper into the ship, they discovered the last log entry was dated 8:00 am on 25 November, nine days earlier. It recorded the Mary Celeste’s position nearly 400 nautical miles from where they’d encountered her. The cabins were noted as being wet and untidy from water but otherwise in reasonable order. In the captain’s cabin, the mates found some personal items scattered about but only some shipping papers and navigational equipment were missing. There was no signs of violence or any other indication why the crew abandoned the ship.

Investigations were launched with all sorts of various theories being thrown around for what happened to the captain and crew of the Mary Celeste. Everything from piracy and involvement by Morehouse and his crew to a theory that the crew got into the alcohol, became stark-raving drunk, killed Briggs and his family, and fled the ship. In all cases, no evidence could be found to support the theory. The prevalent theory, that Morehouse was somehow involved, was dismissed after being thoroughly investigated although it was a theory that hounded Morehouse and his crew for the rest of their lives.

With no sign of the crew, what caused them to leave the Mary Celeste? There was no indication of fire or threatening weather, nothing that would have instantly forced them off the ship without time to note the event in the ships log. No letters were found to be mailed to family back home. Some speculate that the cargo may have become unstable and vapors were drifting into the ship, causing the captain to fear an explosion. This would explain why a crew would leave a seaworthy ship packed with supplies but someone surely would have noted the abandonment in the log. Speculation was rampant but still to this day, no one knows exactly what happened to the people on the Mary Celeste.

After she was moved out of impound and was allowed to sail again, the Mary Celeste suffered from a horrible reputation. Legend and stories of bloodshed and curses haunted the ship. She was sold and sold again, each time at a loss, as no sailor wanted to work her. After another captain of the ship died, the owners sold her again and the new owners tried to make an honest run with the ship. In November of 1884, the owners conspired with shippers who filled Mary Celeste with worthless cargo and misrepresented the value of the goods on the shipping manifest. The captain deliberately ran the ship aground near Haiti, wrecking her beyond repair and ending the useful life of the cursed ship.

Could the Mary Celeste have been cursed from the beginning? Legend says that if the captain dies on a maiden voyage the ship will be cursed and Mary Celeste did suffer hardships throughout her life. The disappearance of Captain and Crew, along with the captain’s wife and daughter, leaving behind a son, has caused much speculation as to what happened on the ocean in 1872. Yet another mystery for a mysterious ocean, the Mary Celeste shows us that no matter how much we know, there are forces working out there that are beyond our comprehension.

To see how the story of the Mary Celeste and other nautical mysteries have influenced my writing, head over to www.leifericksonwriting.com and purchase my books today.

Hicks, Brian (2004). Ghost Ship: The Mysterious True Story of the Mary Celeste and her Missing Crew. New York: Random House. ISBN 978-0-3454-6665-5.

Fay, Charles Edey (1988). The Story of the Mary Celeste. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-4862-5730-3

Hastings, Macdonald (1972). Mary Celeste. London: Michael Joseph. ISBN 978-0-7181-1024-6.

Fanthorpe, Lionel; Fanthorpe, Patricia (1997). The World’s Greatest Unsolved Mysteries. Toronto: Hounslow Press. ISBN 978-0-8888-2194-2.

Leave a reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.